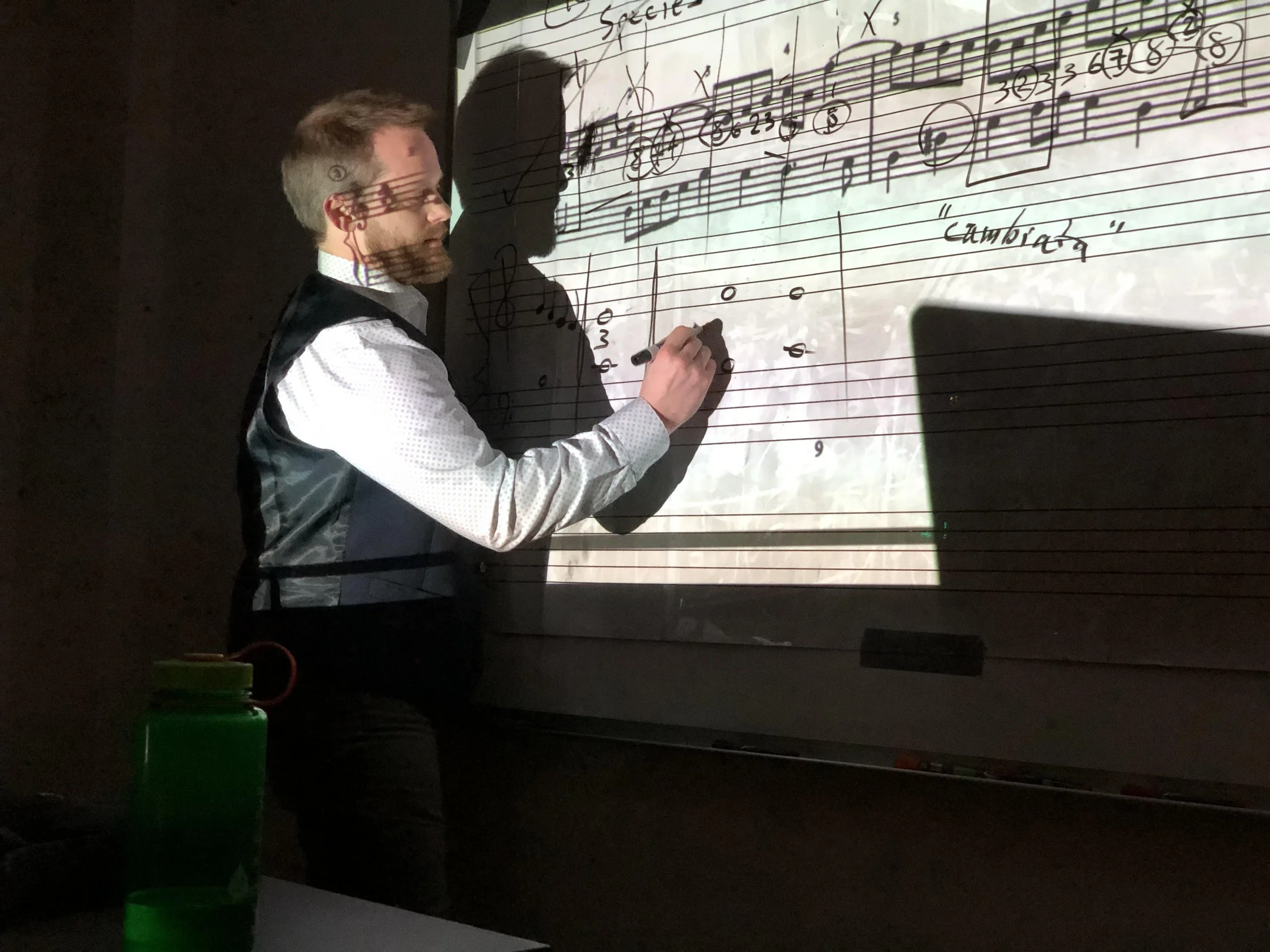

Teaching Counterpoint at the Diocese of San Jose (2019)

SJSU courses:

MUSC202: Graduate Seminar in Music Theory & Analysis

MUSC1A-4A: Music Theory I, II, III, & IV (revised curriculum 2025)

MUSC1B-4B: Musicianship (Aural Skills) I, II, III, & IV (revised curriculum 2025)

M38-138: Applied Composition

MUSC104: Counterpoint

MUSC102: Orchestration

Recent teaching accomplishments:

Nominated for Outstanding Lecturer Award (University-wide, 2023)

National Association of Schools of Music (NASM) Featured Panelist in discussion on pedagogical techniques for “underprepared” students in music theory and aural skills (2023)

Faculty Special Consultant for revising theory/aurals curriculum since 2021

Showcasing student music theory compositions inspired by current trends in a college-wide event, Pandemic Pandemonium so that students feel more connected with the class material and with one another

Creating and administered the online freshmen and graduate music theory placement exams using Musition/Auralia, and continue to use this software in classes

Teaching Composition

Composers must become fluent in the instruments they write for, cultivate a working knowledge of contemporary repertoire and techniques, develop a distinctive voice, and refine their sense of musical proportion. They must take the utmost care in producing professional-level scores, build a visible online presence, pursue competitive opportunities, and navigate the social dimensions of a career that lead to commissions and performances. Student composers require authoritative guidance, unwavering support, and fearless encouragement—and I strive to be their steadfast champion.

Pre-composition: A-Motive-A-Minute, Content and Momentum

Richard Wernick taught me the value of generating a wide range of pre-compositional material before beginning a new work. He once advised me to sit for twenty minutes and force myself to notate one new motive each minute. “In the end, you’ll have twenty motives—many of which might be hogwash—but at least one or two will spark something,” he said. Another assignment involved analyzing the twelve-tone row from Berg’s Lyric Suite—and the piece itself—and deriving new motives and sonorities from it for use in my own composition. This process of “pre-composition” required that I not begin writing until I had built a sufficiently large and varied pool of workable material, or until I had exhausted the tone-row permutations. The result was Berg Variations (2005) for piano—a thirty-minute, minimalist, tonal work that bears little stylistic resemblance to Berg, and was never meant to. Yet the disciplined process of transforming material in multiple guises provided me with a lasting sense of compositional fluency and momentum. It is a strategy I continue to use and teach today—one that gives my students both substance and direction when facing a blank page.

Idea and Execution: Helping Composers Realize Their Ideas (Not My Ideas)

I teach composers that the best music—regardless of style—arises from the marriage of inspired ideas and consummate craft. It is one thing to envision a compelling concept for a piece, but quite another to realize that concept with clarity, depth, and precision. I aim to model this synthesis through my own work, sharing recordings and scores in lessons, seminars, and live performances.

One of my most influential teachers, Sven-David Sandström, embodied this philosophy. In weekly composition seminars at Indiana University, he would play his own music, discussing both his inspirations and compositional techniques. Listening alongside him was electrifying—he would often close his eyes and move to the rhythmic drive of his pieces, fully inhabiting the sound world he created. Beyond the classroom, his generosity extended into the social sphere; he often joined students after class, continuing conversations over nachos and Glenlivet Scotch.

Sven-David’s teaching was distinctive because he invited us directly into his creative process. I learned not only to understand his musical gestures but to emulate and transform them in my own voice. He showed me how to notate sound, where to experiment, and when to take risks. Above all, he valued individuality. His mentorship taught me that true pedagogy balances demonstration with freedom—an approach I now strive to embody with my own students.

My goal as a teacher is to help composers realize their musical ideas with clarity and conviction. When a student brings in an inspired concept—say, a setting of a striking text—I encourage them to begin by analyzing the poem: circling evocative words, sketching verbal descriptions, and jotting motivic ideas in the margins. “Write all over it,” I tell them. From there, we discuss practical matters such as voice type and instrumentation, and I suggest a few exemplary works to study. The student then returns with an assortment of musical sketches, and together we identify which ideas have the strongest potential.

The instructor’s crucial role is to help students recognize and refine their best material through musical reasoning and imaginative demonstration—whether by singing, producing sounds, or illustrating ideas at the piano. I aim to guide students gracefully toward their most compelling solutions through logic, intuition, and example. In the end, I often say, “That’s what I would do—but it’s your piece.” Empowering students to make final creative decisions fosters confidence, ownership, and artistry.

Tricks to Avoid Writer’s Block

Sometimes, the notes simply don’t come. Self-criticism can paralyze even the simplest musical idea, silencing creativity altogether. Fortunately, there are countless ways to rekindle inspiration—techniques passed down to me or discovered through experience. Among them are Richard Wernick’s “motive-a-minute” exercise, using online random-note generators to spark new connections, or setting the ambitious challenge of completing an entire piece overnight. I was happily pushed into this last method during my doctoral studies at Indiana University and later at The 48-Hour Opera Festival. Each of these approaches reminds both me and my students that creativity thrives not on perfection, but on persistence.

Don Freund—my composition professor, dissertation advisor, and pedagogy mentor at Indiana University—taught me invaluable lessons about building compositional skill through constraint. In his first-year composition seminar, he assigned weekly exercises that challenged students to create music within sharply limited parameters, revealing how much can be expressed with minimal means. One assignment required a fast, monophonic piece written entirely in sixteenth notes, using only half-steps, no repeated pitches, and a fixed length of twelve measures in common time. It was astonishing how much expressive variety could be achieved through dynamics and tessitura alone.

One of my favorite techniques from Freund—one I still teach today—is what he called canvas composition. The idea is to compose large-scale sections of music quickly, without becoming lost in detail, thereby establishing a broad structural “landscape,” much like a painter’s background wash. Once that canvas exists, the composer can return to refine, edit, and add foreground material. Even a rough first draft with a double bar line creates momentum; it transforms the blank page into a living work ready to evolve.

Teaching Beyond Craft

Beyond lessons in craft, composers must learn how to build and sustain relationships with the musicians who bring their works to life. They need to understand how to lead constructive, efficient rehearsals and communicate clearly with performers. Much of this growth happens during student composition recitals, where I encourage students to take ownership of every aspect of preparation and performance. I also urge them to apply to programs such as the Minnesota Orchestra Composer Institute, the Mizzou New Music Summer Festival, the 48-Hour Opera Festival, and similar training environments that strengthen both their artistry and professionalism.

Teaching composition extends well beyond nurturing creative concepts. I work closely with students to produce clear, professional scores—helping them refine notation, formatting, and even titles. We discuss practical details such as binding methods, paper types, and score dimensions. Together, we design cover pages, craft program notes, and I personally help spiral-bind their final scores at the end of the semester. I encourage students to self-publish rather than rely on costly engraving services, drawing on my own experience as the 2012 Subito Music Composer Fellow and as a music engraver for Subito Music.

In addition, I emphasize the importance of a strong online presence. My students create SoundCloud and Issuu accounts, and advanced students build personal websites to share their work. All of my composition students become members of ASCAP, allowing them to register compositions and collect performance royalties. I also introduce them to scrolling-score platforms such as Scorefolio, which enable them to publish professional-quality videos of their music on YouTube. By integrating artistic vision with practical career tools, I aim to prepare emerging composers for sustainable, independent creative lives.

Know Your Composers

Composers must engage deeply with the musical works of both the distant past and the vibrant present. It is essential—and often inspiring—to study the recent winners of the Pulitzer or Grawemeyer Prizes, exploring their techniques and ideas as models of contemporary excellence. Yet I also encourage my students to seek out composers who have not received major awards, for recognition alone does not define artistic worth. Expanding one’s listening in this way can sharpen aesthetic awareness and ignite creative direction.

After all, it is difficult to write something truly original amid concert halls filled with so many great ideas—but it is even harder to create authentically without first knowing what has already been done. I tell my students that it is far better to stand tall and knowledgeable on the marble shoulders of Beethoven than to remain in shadow and ignorance.

Keep Composing

Developing a unique compositional voice takes time—often a lifetime. The only true path to mastery is through persistence: continually learning from mistakes and building upon experience. Despite the trials and setbacks I have encountered, I have always returned to this art we call composition. For reasons I cannot fully explain, it continues to bring deep fulfillment, even when no performance lies on the horizon (though I often perform my own works).

I like to end with a simple expression I often share with my students, a bit of wisdom from Jennifer Higdon: “Keep composing.”

Lecture-recital of Variations Promethean at the Mountain View Center for the Performing Arts (2018)

Teaching Music Theory

Since 2019, I have served as a Lecturer in Music Theory and Composition at San José State University, where I have taught courses in theory, musicianship, and composition. With more than twenty years of teaching experience and over a decade in the Bay Area, I approach teaching not simply as a profession but as a lifelong avocation—one that continually inspires me to learn, refine my craft, and share the infectious joy of music with others.

Each semester, I teach a diverse student body whose circumstances demand patience, compassion, and adaptability. Some students cannot afford required course software; others face challenges with attendance or make-up assessments. Through these realities, I strive to maintain calm, empathy, and consistency—guiding each student toward success while fostering a classroom atmosphere of mutual respect and light-hearted community.

In demonstrating theoretical concepts, I draw on both the European Classical canon and a wide range of contemporary and popular genres, including video game music and artists my students admire. Featuring their musical icons empowers them and helps reveal the universality of musical principles. For example, modulation can be traced throughout history—from Bach to Beyoncé. In this way, core theoretical concepts are shown to be vital to all music, bridging the works of student icons and canonical composers alike. When I was a freshman, my own theory professor connected course material to Beethoven’s sonatas—the very work I was performing at the time. That moment transformed abstract theory into living, relevant art. I aim to spark that same excitement in my students, helping them see how music theory illuminates all the music they love. In my classes, if it’s good music, it belongs there.

To make course content more engaging, I design collaborative projects that help students connect with one another. In my aural skills classes, for example, students participate in Duet Relays, exchanging phrases from an assigned Classical melody in a playful, interactive format. Because shared experience is one of the most immediate ways to build community, I also ask students to apply solfege to their favorite pop songs and perform them in class. Pop Song Solfege is always a hit: students bond through their shared musical tastes while reinforcing theoretical concepts through practical application. The exercise challenges them to think analytically about familiar music—identifying form, phrasing, and harmonic structure as they decide where to begin singing. Rarely have I seen such active participation in a prepared singing course. Beyond strengthening musicianship, this activity allows me to learn more about the artists who shape my students’ listening habits. With assignments like these, I aim to transform ear training from a class students have to take into one they want to take.

In my theory classes, students become composers. In Theory III, which focuses on chromatic modulation, I design in-class composition exercises that set poems such as Langston Hughes’s “Dream Deferred” as simple chorales. We begin by discussing the text and exploring how its emotional shifts might be mirrored through harmonic change. When we reach the line, “Or does it explode?”, students often propose dramatic modulations to capture its intensity. Together, we experiment with harmonically adventurous progressions, and the music begins to take shape organically. Students leave class energized to develop their final projects, discovering how theoretical tools can serve expressive, socially engaged art. By connecting technical mastery to meaningful texts, this exercise transforms theoretical study into creative practice.

Guest composer lecture at the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance (2016)